By Peter Hodgson of Walsh’s Financial Planning

The 2019/20 financial year began with strong momentum across most financial markets. However, as the year progressed, unemployment drifted higher and, coupled with benign inflationary pressures, many countries began to lower interest rates further in response.

As the financial year headed towards March, COVID-19 rapidly spread across the globe, with containment measures shutting down entire economies. The impact of this economic shutdown appears to have reversed much of the economic and financial progress over the last few years and the world now finds itself in unprecedented circumstances.

Major economies are now focused on delivering stimulus to support stability as the world battles containment of the pandemic.

Developments in the global economy

Australia

Australia started the 2019/20 financial year with a variety of economic results across the board.

The unemployment rate rose in mid-September to a 12-month high of 5.3%.

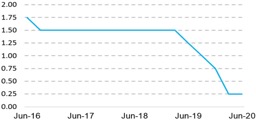

In October, the Reserve Bank lowered the cash rate for the third time in 2019 by 25 basis points to a record low of 0.75%. This was in a bid to decrease the unemployment rate and push both the low and stubborn inflation readings back into the 2-3% target band.

By November, the economy had delivered a back-to-back current account surplus of $7.9 billion (1.6% of gross domestic product (GDP)) for the September quarter – the first consecutive surplus in 46 years – an improvement on the $4.7 billion surplus for June 2018. Key drivers were higher levels of export earnings centred on rising commodity prices.

Also, in November, the Reserve Bank interest rate policy intervention seemed to be working, with Australian employment posting its biggest monthly gain in 15 months. This was led by a surge in part-time jobs. Over November, there was a net gain of 39,900 jobs, more than offsetting the 24,800 drop in October. The unemployment rate marked lower to 5.2% and the participation rate remained stable at 66.0%, near its record high of 66.2% in August.

As the calendar year closed, the economy showed continued resilience, recording another trade surplus in December, rounding out two straight years of monthly surpluses.

As 2020 began, Australia was hit with a devastating summer of bushfires impacting on domestic travel and commerce. Moody’s Analytics reported the economic damage exceeded the $4.4 billion record set by 2009’s Black Saturday blazes, with an estimated $1.9 billion of related insurance claims.

In the wake of this loss, the Chinese city of Wuhan experienced an outbreak of a new strain of coronavirus, officially named COVID-19. Travel restrictions were subsequently placed on parts of China, with Wuhan locked down.

By March, the World Health Organisation (WHO) had declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, coinciding with the Australian Government’s closure of international borders.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cut interest rates in its March meeting by 25bps to 0.50%, which it then followed with a further 25bp “emergency cut” days later reducing the Australian cash rate to a new record level of 0.25%. The subsequent weeks saw a series of virus-related rolling restrictions and lockdown measures ordered throughout the country, forcing many businesses to close or suspend trade.

The April NAB Monthly Business Survey indicated business confidence fell 64 points to 66 in March, its lowest level in the history of the survey which began in 1997. The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment similarly recorded the largest monthly decline in its 47-year history over April.

Australian interest rates – June 2016 to 2020 (%)

Source: BTIS/Bloomberg

As COVID-19 began to have an impact on the normal activities of businesses and consumers, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported that monthly turnover doubled for toilet paper, flour and pasta, while canned food, medicinal and cleaning products rose by 50%. There was a marked decline in spending in the cafes, restaurants and the takeaway sector. Clothing and department store sales also decreased as social distancing protocols limited the businesses that traditionally relied on primarily person-to-person trade.

On March 30, 2020, the Federal Government implemented the JobKeeper stimulus package to support businesses and individuals impacted by COVID-19. The core aim of the stimulus package is to help limit job losses by allowing employers to retain staff. Those receiving JobKeeper payments are counted as employed as part of overall employment figures, even where they are not working any productive hours.

With more than six million Australians accessing JobKeeper payments across 860,000 businesses, the Federal Government suggested that this would put a floor under and limit overall job losses. The Australian Labour Force survey data indicated that in spite of JobKeeper relief, the decline in market conditions saw unemployment increasing by 1% to 6.2%, a 594,000 reduction in jobs.

Australian unemployment – June 2018 to 2020 (annualised)

Source: BTIS/Bloomberg

By May, the restrictions seemed to be working, with the Australian rate of infection dramatically lowered through state-based education and activity targeting the “flattening of the (infection) curve”. The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment experienced a bounceback of 16.4% to 88.1 in May.

With the pandemic affecting almost every single country, industry and consumer, the Federal Government’s plans to achieve a budget surplus were replaced by the need to deliver a much-needed and immediate substantial economic stimulus.

Australia’s GDP fell 0.3% in Q1 of 2020. While this was the first quarterly reduction in GDP since 2011, the Federal Government announced that Q2 results were forecast to far exceed the downside of Q1’s print. COVID-19 has clearly played a significant role in this result, however, weak performance in private sector demand over the past year has also contributed.

Australian GDP – June 2016 to 2020 (annualised)

Source: BTIS/Bloomberg

Following strict containment protocols of March and April, by June most states began easing lockdown measures with reported new infection rates dropping to a nominal level and businesses eagerly returning to basic trading using social distancing measures. Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy noted a revision to Treasury’s unemployment rate forecast to peak at 8%, instead of 10% as previously thought. However, the official unemployment rate will be released in September when various forms of support, including JobKeeper, are due to end in their current form.

The ABS announced that total payroll jobs increased +1.00% between mid-May and mid-June. The expected budget deficits for 2019/20 and 2020/21 have now been revised to $95 billion (4.8% of GDP) and $240 billion (12.2% of GDP) respectively. This significant increase from $80 billion and $170 billion can be attributed to cyclical deficit, the existing fiscal stimulus, $50 billion worth of new spending and a new $15 billion stimulus package expected to be announced on Budget day.

United States

The 2019/20 financial year saw the US/China relationship and the COVID-19 outbreak take centre stage. Earlier, in August 2019, President Trump’s announcement that the US would impose 10% tariffs on US$300 billion worth of Chinese goods sparked a slide in global equities. The US trade deficit with China widened from US$30.1 billion in June 2018 to US$30.2 billion in July 2019 – a five-month high. US exports to China are down 18.1% year to date (YTD), while imports had fallen 12.2% – a reflection of diminishing bilateral trade.

During September, global oil prices surged after an attack on Saudi Arabian oil facilities that accounted for around 5% of global supplies. The US was forced to dip into its Strategic Petroleum Reserves. Headlines surrounded President Trump’s September impeachment proceedings, however the news had only a mild impact on financial markets, with the S&P500 falling 1% over the five days after the announcement.

The enhanced prospect for a temporary US/China trade deal seemed to preoccupy markets as calendar year 2019 drew to a close. Another promising note for trade was the partial trade agreement signed between the US and Japan on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly, easing tensions between the two nations. In October, the US Federal Reserve cut its policy rate by 25bp to a range midpoint of 1.625% – the third consecutive reduction.

By December, it was announced that the US and China had reached a “phase one” trade deal just prior to new tariffs coming into effect, that would have affected a mass of consumer goods. The US had therefore decided not to progress with 15% tariffs on US$160 billion worth of consumer goods which were scheduled to take effect on 15 December.

Over February, COVID-19 was spreading across the world rapidly with parts of China already in a hard lockdown. Apple warned of the potential for a global iPhone supply shortage resulting from its Chinese factories being shut due to the outbreak.

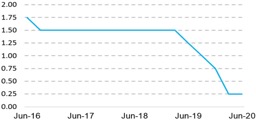

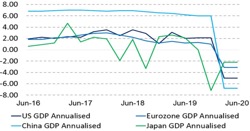

In March, the US congress and the Trump administration reached an agreement of a US$2 trillion stimulus package to protect the economy from COVID-19. The stimulus amounts to 10% of GDP. Over Q1 of 2020, the United States’ GDP decreased by 1.2%, representing the most significant decline since late 2008, and its first drop in six years. This decrease was heavily concentrated in late March, associated with the lockdown measures implemented to contain COVID-19.

A significantly worse Q2 is expected for the United States, with initial results from Q1 confirming this likelihood.

US, Eurozone, China and Japan GDP – June 2016 to 2020 (annualised)

Source: BTIS/Bloomberg

In April, the Federal Reserve (Fed) announced it would commit to unlimited government bond purchases. The Fed surprised the market by saying it would also buy investment grade corporate bonds and high yield bonds (provided that the issuer had an investment grade rating prior to 22 March).

April also saw jobless claims hit 30 million in the United States – an increase of alarming and unprecedented proportions in comparison to the historically low levels of unemployment announced in January.

The fallout from the reported killing of George Floyd dramatically altered the COVID-19 conversation throughout June. The ensuing Black Lives Matter demonstrations across the United States (and the world) saw protests and anti- establishment sentiment spread rapidly. Just as economies were beginning to open, many US cities were being placed into lockdown, with the White House threatening the possibility of a declaration of Martial Law.

June saw infection rates of COVID-19 begin to increase throughout the United States once again. US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin said that the US should not shut down the economy again even if cases escalate. The US Department of Labour announced that non-farm payrolls were up +4.8 million over the course of the month.

Additionally, the unemployment rate decreased from +13.3% to +11.1% as more lockdown restrictions were eased.

Tensions between the United States and China continued throughout June. For the first time in six years, the US Navy sent two aircraft carriers, part of the Nimitz Carrier Strike Force, to the South China Sea as a show of force.

Asia

The 2019/20 financial year saw China’s economic standing heavily affected by both US tensions and COVID-19.

In August, China announced increases of 5-10% in tariffs on US$75 billion of US imports, plus tariffs for restoration of up to 25% on vehicles and parts. The ongoing trade conflict with the US impacted production activity in China in particular, with consumer spending and investment spending not compensating enough to offset the decline.

During October, Japanese exports fell 9.2% from a year earlier, with sharp declines in all of Asia. Imports fell by 14.8% in the year. Weakening global demands and trade tensions were to blame. Japan faced more headwinds from a sales tax hike with the economy lacking in key growth drivers.

In January, the outbreak of COVID-19 sent shockwaves through the global financial markets, with increasing levels of uncertainty evident in China and other regions. The World Health Organisation declared COVID-19 a “public health emergency of international concern”. This resulted in quarantine and travel restrictions being imposed across the Chinese Tier 2 city of Wuhan as authorities attempted to prevent the spread of the virus.

The response to stem the spread created a drag on economic activity in China and its neighbours as infrastructure networks were closed and residents were confined to their homes. The outbreak came at a period when the Chinese economy was seeing signs of stability due to prior monetary and fiscal policy enactment.

February saw extreme quarantine restrictions closing down the majority of factories, with public gatherings across much of the Asian region banned. Containment efforts affected demand and supply chains on manufacturing as companies were running below capacity. Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea outlined fiscal measures to aid affected sectors. Factory output across several Asian countries slumped to record lows in April, signalling a deeper contraction in the world’s manufacturing hub even as China begins restarting some operations.

Global market volatility increased in May, with US President Trump vowing to “take action to revoke Hong Kong’s preferential treatment as a separate customs and travel territory from the rest of China” as well as imposing sanctions on individuals who are caught “smothering” Hong Kong’s freedom. The Chinese Government continued to ease restrictions to return to normal economic activity in mainland China. Progress was slow, with the industrial sector plateauing in its recovery. While most businesses are now back to work across the country, only a fraction are operating at or near full capacity.

As the financial year closed, economic activity has been continuing to recover in China. Growth in industrial production edged up from an annual rate of +3.9% to +4.4%. However, the increase was still below consensus. Retail sales were still in decline but improved from an annual growth rate of -7.5% in April to -2.8% last month.

The data highlights a steady but slow recovery in the Chinese economy. A survey conducted by the Bank of Japan determined that big manufacturers’ confidence decreased to levels last realised during the GFC. India’s economy is projected to have contracted by -20.6% in the three-month period leading to June. While the Indian Government have implemented stimulus packages worth about 10% of GDP, the spread of infection remains difficult to control.

Europe

In July 2019, Boris Johnson emerged victorious in securing office from Theresa May as the new Prime Minister of the UK, raising the likelihood of a hard Brexit on 31 October.

Political risk became the focal point of European markets in late August as Italy’s Prime Minister Conte resigned, ending the League/5-star coalition. Conte blamed the country’s political crisis on the “irresponsible” Deputy Premier Matteo Salvini.

The snap December UK election saw a dominant Boris Johnson led a Conservative Party victory, providing a strong mandate to deliver his promised exit from the European Union (EU). In January, the UK officially left the EU after 47 years of membership, with Brexit officially occurring on 31 January. The departure came three years after the country voted by a margin of 52-48% to walk away from the EU, which it joined in 1973. Prime Minister Boris Johnson is currently undertaking 11 months of talks to agree on a trade deal before the transition period ends on 31 December. The UK will continue to follow EU laws during the transition period.

January saw the 50th annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Switzerland. Business, government and invited members of civil society gathered to discuss the most pressing global issues with a view to improving the state and future of the world. The overarching theme of the event was climate change and the challenges of building more sustainable economies.

During February, Italy was the first European country to experience a severe COVID-19 outbreak. The Italian Economic Minister announced a €3.6 billion stimulus package to mitigate the impact of the coronavirus outbreak for the economy and the affected population. Re-elected Italian Prime Minister, Giuseppe Conte, announced the most stringent restrictions on freedom of movement imposed in Europe since World War II. Sixty million Italians were only allowed to travel for pressing reasons of work, health or other extenuating necessities (with written permission). Italy became the first country to attempt a nationwide lockdown, which has since been followed globally. The Bank of England cut its key rate twice over March by 50 basis points initially, then by a further 15 basis points to 0.10%.

In April, reports emerged that Europe experienced a downturn to a degree not seen since the end of World War II. It was announced that the total sovereign debt from European member countries would increase from 86% of GDP last year to above 100% in 2020. The Bank of England anticipated British GDP would decrease by 14% this year, which would be the most severe recession since the Great Frost in 1709.

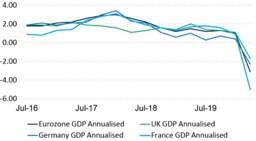

Italy, which was one of the first and hardest hit by COVID-19, announced a recession in Q1, with GDP reducing by 4.7%. Additionally, Germany and France were considered to already be experiencing a technical recession. The German economy decreased by 2.2% while French GDP shrank by 5.8% in Q1.

Eurozone, UK, Germany and France GDP (Annualised) – June 2016 to 2020 (%)

Source: BTIS/Bloomberg

Throughout June, the first wave of COVID-19 infections across Europe appeared to be subsiding. While there were some new, smaller outbreaks across the region, most restrictions were being eased. The EU announced it would open its borders to 14 “safe countries”, including Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea and Thailand.

Confidence in Europe continued to improve during June. Economic confidence rose in May from 67.5 to 75.7, although it remained well below the plus-100 readings reported before the pandemic’s outbreak in February.

Highlights of the developments across markets over the financial year

Evident from the market and economic events over the financial year, we saw the first half of the year deliver strong returns across most key asset classes. As the second half of the financial year moved into February, the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a historical fall in markets, with the velocity of such exceeding what was experienced at the start of the GFC – which eroded all the past years’ strong positive market driven returns by the end of March.

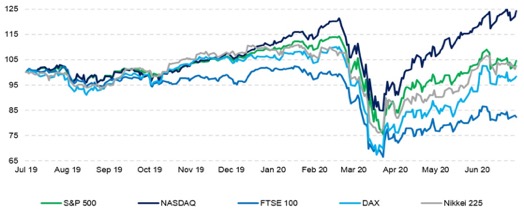

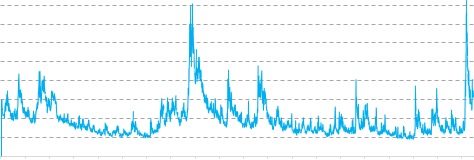

Market volatility Index to June 30, 2020

Over the last three months of the 2019/2020 financial year, markets saw the VIX level, which is a measure of the expected volatility of the US S&P 500’s index options, surpass the historical level reached in 2009 during the GFC. The chart below depicts times of greater uncertainty (more expected future volatility) which results in higher values, while less anxious times correspond with lower values. Generally speaking, when the VIX is high, investors are more likely to pursue lower risk strategies, thus creating downward pressure on equities.

US Market Volatility (Risk) – June 2020 (CBOE:VIX)

Over the third quarter of the financial year we saw the majority of major markets fall in historic proportions as COVID-19 began to be labelled a global health crisis, which collapsed business and consumer activity, and in turn markets. The pace at which markets have recovered over such a short period when compared to previous market falls and rises left many investors entering the market now at higher valuations than before its prior peak. This is particularly the case with US equities (S&P 500) and the impact the Tech sector (measured by the Nasdaq) has had on the recovery

Major Market Indices FY 20 (rebased at 100)

Looking ahead

Governments and central banks are continuing to roll out stimulus measures to reduce the economic damage caused by COVID-19. While the gradual lifting of containment measures across the world has been seen as positive by the markets, the long-term economic damage of the shutdown is still not known.

In Australia, we have now entered our first technical recession in almost three decades and as GDP fell in the first quarter of the financial year of 2020, a further decline in growth is expected in the second quarter.

While we have witnessed a strong recovery in equity markets from the March lows, supported by the benefits of low interest rates and the enormity of spending programs by governments around the world, there are still concerns over the short term.

A rise in unemployment can result in lower productivity and economic growth, particularly if this reflects longer term structural changes in the economy. Countries also face the uncertainty of a possible “second wave” of COVID-19 infections and its potential impacts.

Generally, over the long-term, shares and property continue to provide an opportunity to build long-term wealth. Particularly now, given the continuing low returns on offer from cash and traditional bonds. As always, we support the strategy of diversification when investing, which leaves investors less exposed to a single economic or market event that we have experienced this financial year.